Hawaiian Culture on Haleakala

Ancient polynesians had a tremendous ability to discover the many resources that the natural environment provided. This resourcefulness allowed them to travel thousands of miles on the open ocean on double hulled voyaging canoes that were believed to carry up to 80 people and their provisions which included dried foods, plants and animals. This is how migrants from the southwestern islands arrived and populated the Hawaiian Island chain beginning around 1000 years ago…

One of the most highly honored members of the ancient Hawaiian society was the canoe carver, called a kalai wa’a, and they were an essential part of the Hawaiian society…

An Ancient Quest

Imagine for a moment you’re a teenage boy living on the slopes of Haleakala in the mid 15th century.

Since you were a boy you had a fascination with canoes, the ancient Hawaiian version of a new car. You have lived in your parents Makena Cove Beach & Haleakala Slopes at Ulupalakua seen from Oceankuahale (ancient house complex) with eight other people as a child. At around the age of 9 or 10 (it’s hard to know since Hawaiians didn’t count years of birth) your interest in canoes peaked, so you moved in to live with the canoe Kahuna (expert) where you learned the craft of building and maintaining canoes. Your brother had a similar experience in the forest. He loved being in the ancient forest of koa, ohia and sandalwood trees that towered over 100ft into the clouds along the slopes of Haleakala volcano. Your brothers skills became that of a birdcatcher – their feathers were used to adorn the clothing of the Ali’i (chiefs or ruling class) and this region was renowned throughout the Hawaiian islands for the vibrant colors of Haleakala’s forest birds.

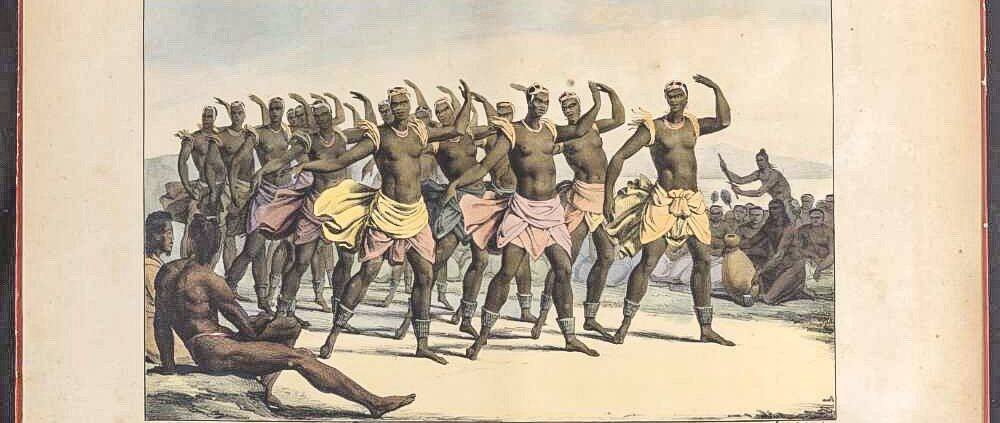

The kahunas (called a Kalai Wa’a – canoe experts/teacher and a Kia Manu – bird catching expert) who trained you and your brother have determined, after consulting the stars, the weather, nature signs and time of year, have performed various ceremonies and sacrifices. They have determined that the gods approve and it is time for both you and your brother to venture into the forest to test your skills. You are instructed to consult your own dreams and decide when you are ready to leave on your quest. Soon all signs are in balance and the two of you depart. The drumming, singing and dancing of your village’s kuahale (house complexes) and ohana (family) accompany you as you hike up the slopes towards the towering forests above.

Ascending The Slopes Into Haleakala’s Forest

After a steady climb through grass and shrub covered slopes you reach the treeline by early evening and enter the upper forests. Your brother heads towards the ohia lehua (native flowering tree) grove a short distance away while you search the tall koa trees nearby.

You walk quietly, looking and listening for the perfect koa tree that will become your canoe. You remember in your teachings that if there are many forest birds creating lots of activity and noise in a tree, it could be full of insects and rotten inside. Your kahuna’s training has taught you that a clean straight tree of around 15 to 20 feet tall and around 2 ½ to 3 feet in circumference with minimal bird activity in and around it is ideal. Having found your tree you gather wood and build a fire.

As the sun begins to set your brother returns with great news of sighting mamo and o’o birds (yellow and rare) and many akakapi and i’iwi (red) birds in his ohia forest area. There is much excitement between you two. You have both found that for which you came. After the fire is kindled you get a chip from the chosen koa tree and burn it in the fire while singing prayers to the canoe gods: to Kupulupulu, Kumokuhali’i, Kuolonowao, Kupepeiaoloa, Kuho’oholo-pali, Kupa’aike’e, Kanealuka, and various others. Your brother does likewise – praying aloud to the forest and bird gods.

Soon you begin cooking the food you brought with you. Pork, which is sacred to the gods, is cooked as an offering and as a meal. Sweet potato, poi (taro root pounded to a paste) breadfruit, lau lau (fish,salt & pork fat wrapped in taro leaves and steam cooked by your family) and some ohi’a ‘ai (mountain apples) you picked along the way will hopefully last the two to three weeks you’ll be here in the forest. You then eat the food you’ve prepared and offer some to the gods. You take great care in attending to the rituals and protocols for cutting a koa tree. Failure to get it right could result in a cracked canoe.

You’ve spent months fashioning your first stone adze (sharpened basalt rock and attaching it to a handle) in anticipation of felling this tree and carving your first canoe. As a strong young man using these stone adze it will take you several days to fell the tree. (today a strong man with a steel ax can fell such a tree in half an hour) After digging down to the roots you begin to chisel away at the tree. Carefully you begin to notch the trunk in the direction you have chosen it to fall. The trunk must land in a position that it can first be dug out, then slid down the mountain to the sea.

Ancient Hawaiian Bird Catching

In Haleakala’s Forest

Meanwhile your brother is off to the Ohia forest nearby. He sits in the grove watching the birds, taking note of which trees they frequent at what times. He knows from his kahuna’s teaching that the morning is the most active for the birds. He selects several trees which he will return to in the morning to set his trap.

He also notices beaten paths in the forest. These are wild boar trails that he will also position a snare upon. Catching one of these hogs will feed the two of them for the several weeks that they plan to be here in the forest. They have food for a few more days so he will wait to set his trap. No need to spook the animals until they need to catch one. He also finds a spring (his kahuna told him of it’s location) and fills his gourd calabash to bring back to his hard working wood chopping brother.

On his way back he stops to admire the view, giving thanks and offer prayers to the gods as he looks down the slopes towards the ocean. From this elevation he can see three islands; Kahoolawe directly ahead, the Big Island to the left, Lana’i just beyond Kahoolawe and the West Maui Mountains to the right. The sweeping view is as spiritual to him as it is beautiful. He sings a chant to the gods as he nears camp, alerting you of his presents.

As the days go by your brother returns every day with captured birds. His kapa cloth bag begins to fill with red feathers. A smaller bag holds the coveted yellow feathers of the O’o, Mo’o and Mamo. The Akakani and i’iwi (red) birds are plentiful. These he will skin and eat. The rare yellow birds have kapu (restrictions) against killing them so they are plucked of a few precious feathers and released.

Tree after bird active tree he snaps off the ohia blossoms leaving only a few fuzzy red flowers on perfectly placed branches. Coating these branches with the sticky sap from the ulu (breadfruit) he brought, he works his way back and forth across the forested slope. The stuck birds are gathered up, released from their sticky trap with kukui nut oil, an oil also used in their stone candles to light up the family home at night. He is quickly mastering the art of bird catching and returns to camp each midday to excitedly show his catch of the day.

A Canoe Is Born

Days go by as you spend mornings and evenings chipping away at the tree. Mid days are hot and you have been trained to rest and recuperate during these times while waiting for the cooler temperatures of the evening.

Having finally felled the tree and chopping off the upper part of the trunk you stand back and admire

your log which is roughly 15 ft long. This will be a small canoe, unlike the larger voyaging canoes that can measure 100 ft long and often requires the work of hundreds of men accompanied by the Kahuna Kalai Wa’a who chooses the trees, performs rituals, and directs the building of these massive double hulled canoes.

This small canoe will be the deciding factor of whether you will continue down the path to becoming a Kalai Wa’a yourself one day. You begin chopping down the center of the log – laying out the line to be dug out. You work steadily knowing that your Kahuna shall arrive soon with a crew of workers to help bring the partially carved log down the mountain. Singing and chanting as you work, you can’t help but feel the divine mana (spirit) of your ancestors who have been carving canoes for thousands of years.

After many days of hard work burning, chopping and shaping the inside of the log, a group of a dozen men from your village arrive with your Kahuna Kalai Wa’a (canoe expert). They assess your efforts with approval and begin digging an imu (underground oven) which will be used to cook a pig to honor the gods and you for a successful trip into the upland forests of Haleakala. Before heading back down the mountain dragging the partially shaped canoe to the sea shore, the group gathers many other items needed to complete the canoe.

Ancient Hawaiian Stone Tools

It is high on this mountain that the dense basalt lava stones will be gathered to create over one dozen different stone adze that are used in all the stages of canoe carving. You hike upslope to these exposed outcroppings to gather the stones used for over 15 different kinds of adze tools used to carve and finish your canoe.

Adzes (list from Tommy Holmes, The Hawaiian Canoe, p.27)

- ko’i ‘ahuluhulu: planing adze for rough lumber

- ko’i alahe’e: hardwood adze

- ko’i ‘auwaha: scoop adze

- ko’i ‘awili: socketed adze

- ko’i holu: broad, bent adze; used to shave off smooth in the direction of the grain

- ko’i ho’oma: narrow and deep adze

- ko’i kahela: chisel

- ko’i kaholo: planing adze

- ko’i kalai: carving adze

- ko’i kapili: finishing adze

- ko’i kikoni: small finishing adze; used to shave off and smoothen the wood surface

- ko’i kila: steel adze (post European discovery)

- ko’i kukulu: straight-edged adze; used to shave down canoe sides

- ko’i kupa: adze used for hollowing out the canoe hull

- ko’i kupa ‘ai ke’e: swivel-headed adze; used for narrowing out the hollow bow and stern sections, smoothing and polishing

- ko’i kupele (pele): adze used to hollow out bottom of canoe hull by cutting zig-zag trenches; to scoop out

- ko’i lipi: sharp adze; used for hewing koa trees

- ko’i meki: iron adze (post European discovery)

- ko’i milo: adze used on the outside of canoe

- ko’i nunu: “greedy” adze; same as ko’i kalai

- ko’i ‘ole: conch shell adze

- ko’i’ oma: small, oval adze; used for finishing

- ko’i ‘opaka: adze used on the outside of canoe; cuts smoothly

- ko’i ‘owili: gouge; twisting adze; same as ko’i kupa’ai ke’e

- ko’i pa’ahana: adz for shaping hull

- ko’i pahoa: chisel; “dagger” adze

- ko’i paukuku: adze used to cut canoe log into sections

- ko’i wili: socketed adze

Other Tools

- ‘ana: pumice; used for rubbing

- ‘eleku: coarse basalt; used as a polishing stone

- ‘oahi or ola’i: rough stone, pumice, or coral rock for polishing

- ‘o’io: close-grained basalt; used for polishing

- pohaku ‘anai wa’a: finishing stones

- pohaku pao: stone chisels

- pohaku kapili wa’a: stone hammer used to tap chisels in making lashing holes in canoe parts

- puki’i wa’a: wooden clamps

- puna: fine coral; used for rubbing

- wili: drill

Ancient use of Haleakala Forest Plants

Plants are also gathered from this forest; olona and ‘ie’ie (climbing shrubs) will be made into strong cordage for lashing. Olona is also gathered by your brother – used to create a woven netting that will hold the feathers in place on capes and cloaks for the Ali’i (chief or ruler).

The ‘akoko, ‘uhaloa, ‘aka’akai and ‘ana’u plants contain dyes to be used to paint the canoe. These are carefully gathered. Kukui nuts are also harvested for their oil which will act as waterproofing sealant on the canoe hull. The soft wood of the wiliwili tree will also be gathered and used for the outrigger float.

The following is a list of plants and their uses in building canoes.

- ‘akoko: paint, dye

- ‘uhaloa: paint, dye

- ‘aka’akai: paint, dye

- ‘ama’u: paint, dye

- olona: lashing

- ‘ie’ie: lashing

- niu: sennit, water-sealant

- hala: sails, covers

- ipu: bailer

- koa: hull, manu, seats, gunnels, spar, mast, paddles

- ‘ulu: hull, manu, gunnels, seats, caulking

- kukui: hulls, paint

- hau: ‘iako (outrigger boom), ama (outrigger float), boom, paddles

- wiliwili: ama (outrigger float)

The Return Home

References

Hawaiian History References

Mary Abigail Kawenaʻulaokalaniahiʻiakaikapoliopelekawahineʻaihonuainaleilehuaapele Wiggin Pukui (20 April 1895 – 21 May 1986), known as Kawena, was a Hawaiian scholar, dancer, composer, and educator. She published more than 50 scholarly works. She is the co-author of the definitive Hawaiian-English Dictionary (1957, revised 1986), Place Names of Hawaii (1974), and The Echo of Our Song (1974), a translation of old chants and songs.

Her book, ʻŌlelo Noʻeau, contains nearly 3,000 examples of Hawaiian proverbs and poetical sayings, translated and annotated. The two-volume set Nana i ke Kumu, Look to the Source, is an invaluable resource on Hawaiian customs and traditions. She was a chanter and hula expert, and wrote lyrics and music to more than 150 Hawaiian songs.

Samuel Manaiakalani Kamakau (October 29, 1815 – September 5, 1876) was a Hawaiian historian and scholar. His work appeared in local newspapers and was later compiled into books, becoming an invaluable resource on the Hawaiian people, Hawaiian culture, and Hawaiian language during a time when they were disappearing.

Along with David Malo and John Papa ʻĪʻī, Kamakau is considered one of Hawaii’s greatest historians, and his contributions to the preservation of Hawaiian history have been honored throughout the state of Hawaiʻi

In 1961, the Kamehameha Schools Press published Kamakau’s first two series as a book entitled Ruling Chiefs of Hawaiʻi. Three years later, in 1964, the Bishop Museum Press published his last series as a trilogy, entitled Ka Poʻe Kahiko: The People of Old, The Works of the People of Old: Na Hana A Ka Poʻe Kahiko, and Tales and Traditions of the People of Old: Na Moʻolelo A Ka Poʻe Kahiko. A revised edition was published in 1992

Legends and Myths of Hawai’i by his Majesty King Kalakaua – introduction by Hon R.M. Daggett – Published by Charles L Webster & Company 1888

< ahref=”//storyofhawaiimuseum.com/the-story-of-hawaii/hawaiian-history-moment”>Hawaiian History Moment

Archeological References

Kua’aina Kahiko: Life and Land in Ancient Kahikinui, Maui by Patrick Vinton Kirch – Author & Professor of Anthropology at UC Berkeley

Maui a History – by Cummins E Speakman Jr and Jill Engledow

Shark Going Inland Is My Chief – Author Patrick Vinton Kirch

Unearthing the Polynesian Past: Explorations and Adventures of an Island Archaeologist – Author Patrick Vinton Kirch – UH Press Info

Feathers and Fishhooks – Author Patrick Vinton Kirch

School Resources

Kamehameha Schools – Living Hawaiian Culture site

Mahalo for visiting and taking an interest in the Hawaiian culture…Aloha Nui Loa!